Ice Maze RL Basics#

TLDR

Ice Maze is a discrete fully observable environment with small action space.

This makes it an ideal starting point as it runs simply and is easy to inspect in a debugger.

This example contains implementations of all the key terminology from the intro, particularly some key distinctions.

For example reward vs return.

We choose a slightly more complex implementation of Q learning that includes advantage calculation.

While not necessary for a simple example this will prep us for PPO and GRPO in future chapters.

Ice Maze Challenge#

Ice maze is a classic RL setup, where our hero needs to get to a prize by navigating a maze. In this setup a small agent needs to learn how to navigate a maze with holes in the ice to find a rewards.

The agent can move in all four directions, except when constrained by the board. Eventually the agent either falls in a hole and “loses”, or eventually gets to the prize and “wins”. For us, the folks making the RL Algorithm we have three objectives:

Implement an algorithm where the agent learns to reach the prize

Implement an algorithm where the agent reaches the prizes in the least amount of steps

Ensure the learning is as computationally efficient as possible

Creating our Reinforcement Learning Setup#

For the Ice Maze problem, there are different choices and implementations of RL algorithms that will work. Below we’ll go through one algorithm, called Q Learning, and in this case with a Q table which is just a python dictionary and arrays.

While this simple setup will work with this small problem, with LLMs this simple implementation will not work well with larger models and action spaces. However our focus here is the not specific algorithm or the Ice Maze problem itself, but rather to concretel intorduce the core concepts specific terms we’ll be using later when training LLMs with RL.

Policies#

We defined behavior and target policy in the last chapter, but let’s do so again now that we have a concrete implementation. For the purpose of this tutorial, we’ll choose Q-Learning, which we implement here as an off-policy algorithm. Now, what is an “off-policy” Algorithm? We reintroduce our two definitions first:

Behavior Policy: What the agent is actually doing now (maybe being a bit random to explore).

Target Policy: The “perfect” strategy the agent is trying to learn.

In technical terms:

During training, we’ll use an epsilon greedy behavior policy, which sometimes deviates from the target policy, by definition.

After training, we’ll use the target policy to navigate the ice maze. In particular epsilon is the representation of explore vs exploit, another fundamental tradeoff in Reinforcement Learning. It represents how often we stick with our greedy policy of picking what is believed to be the best action, and how often we randomly do not and do something random.

In the code below, epsilon is the probability of picking a random action.

def choose_action(q_table: np.ndarray, state: int, epsilon: float, env):

"""Chooses an action using an epsilon-greedy policy."""

if np.random.uniform(0, 1) < epsilon:

return env.action_space.sample() # Explore: pick a random action

else:

q_values = q_table[state]

assert q_values.shape[0] == 4

return np.argmax(q_values) # Exploit: pick the best known action

Value and Q-Value#

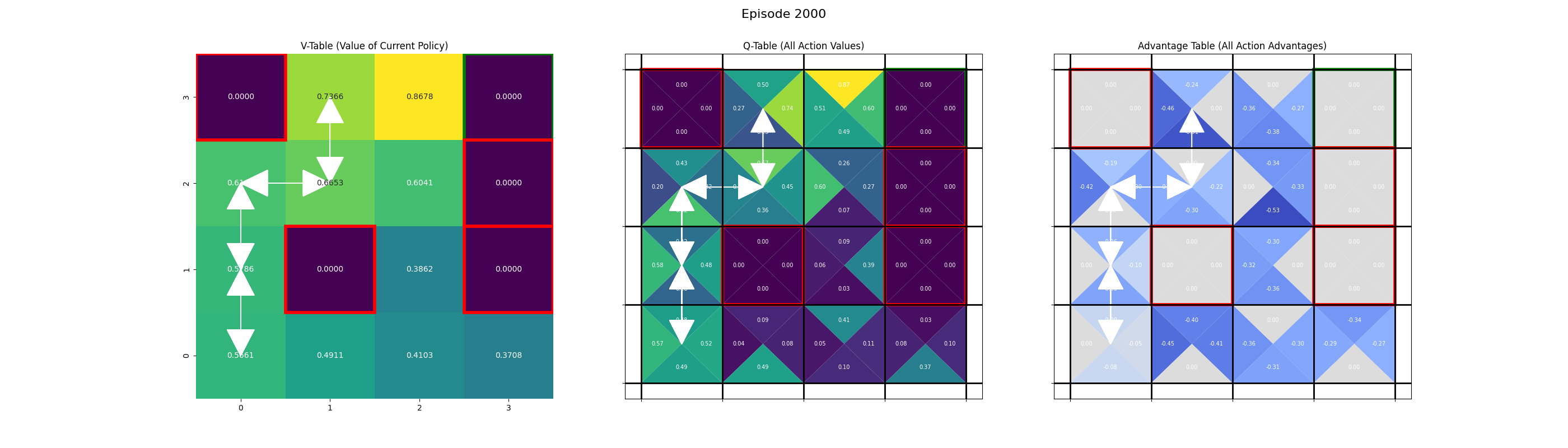

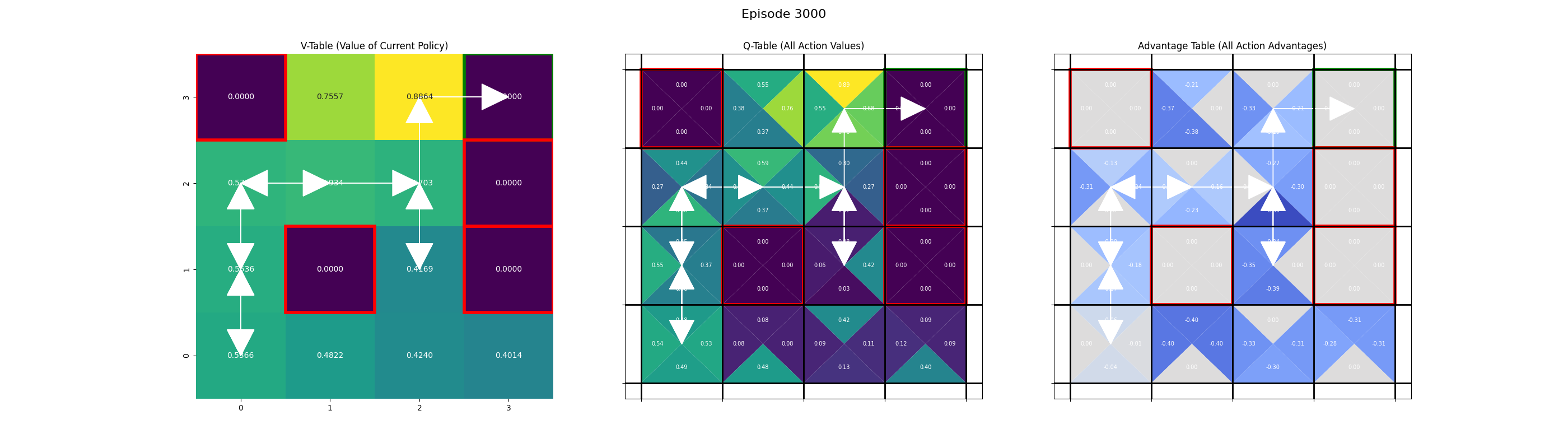

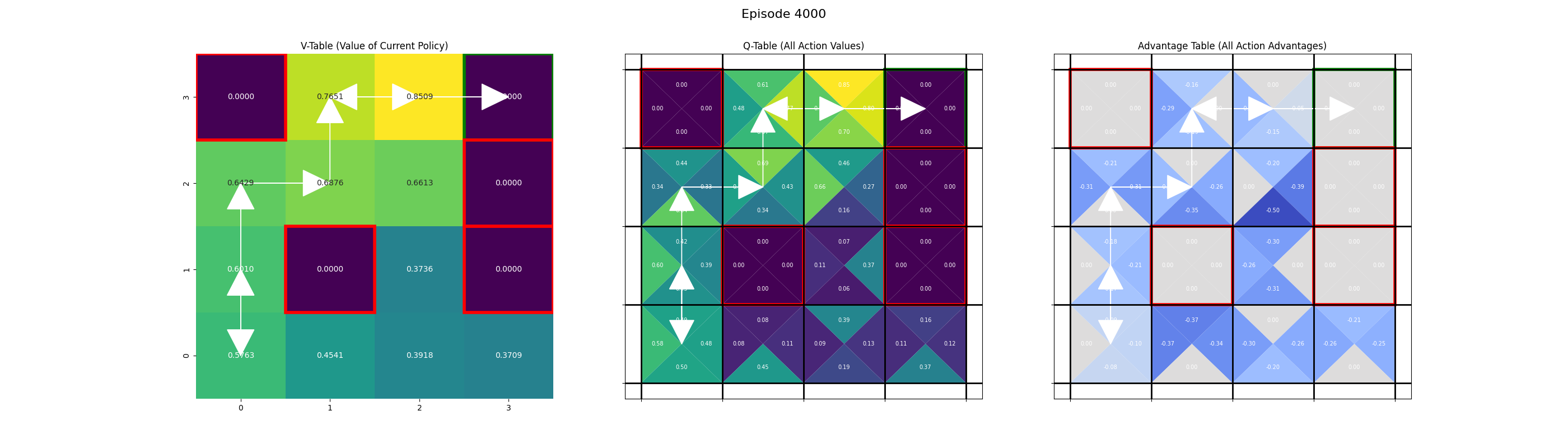

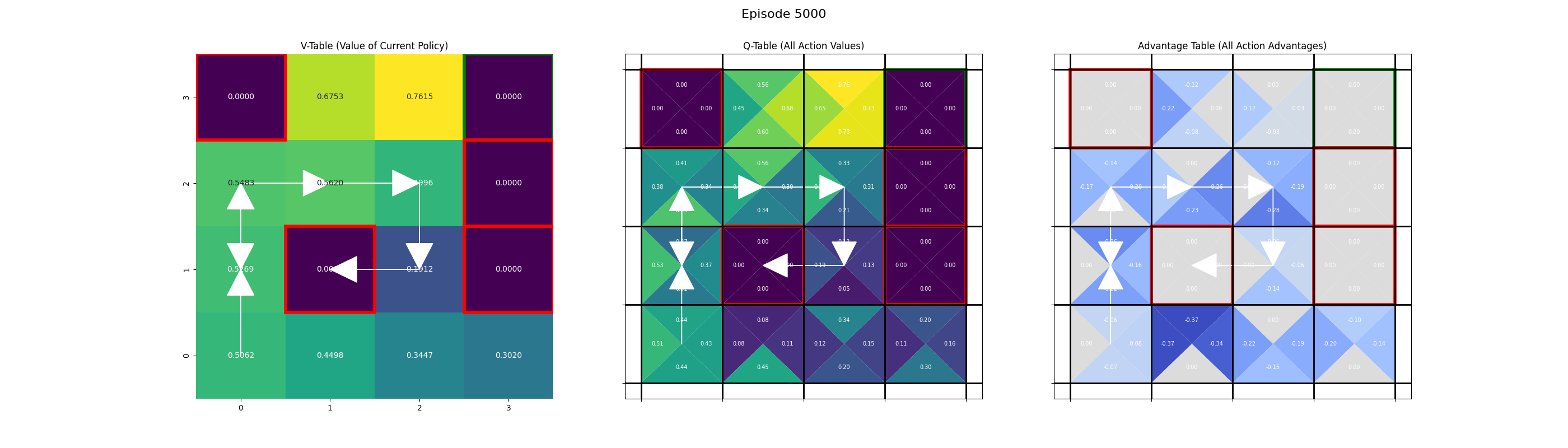

This is the core of where our ice maze agent learns. We need to estimate the “goodness” of being in a state (Value) and the goodness of taking an action in a state (Q-Value).

Quantities that are estimated:

Return (\(G_t\)): The total discounted reward from time-step \(t\). \(G_t = R_{t+1} + 𝛾R_{t+2} + ...\)

Value (\(V(s)\)): The expected return from state \(s\). \(V(s) = E[G_t|S_t=s].\)

Q-Value (\(Q(s,a)\)): The expected return from taking an action \(a\) in state \(s\). \(Q(s,a) = E[G_t|S_t=s, A_t=a].\) In our simple example, we update these values in a simple lookup table (a numpy array). The important concepts here are how “strongly” we update the values based on the reward given from the environment. For this algorithm we have:

Discount Factor (𝛾) – How much to discount future rewards#

We need it to account for uncertainty: the further into the future a reward is, the less certain we are that we’ll actually get it. A value close to 1 (in practice, usually between 0.9 and 0.99) means we value future rewards highly. Conversely, if \(\gamma = 0\), the agent is purely “short-sighted” and never learns to sacrifice a small reward now for a huge one later. Concretely, \(\gamma = 0.9\) means a prize is worth 10% less for every extra step the agent takes to get there.

Learning Rate (𝛼) – How quickly to update our Q-table#

The environment is often stochastic: you might take a good action but fail anyways. If \(\alpha\) is small, you won’t immediately decide that action was bad; you’ll wait to see if you fail consistently in these conditions before lowering the Q-value. If the environment has less randomness, we can afford to have a higher \(\alpha\). In short: A high learning rate means we give more weight to new information, approaching a memory-less agent as \(\alpha \to 1\). Conversely, if \(\alpha\) is close to 0, the agent is stubborn.

NB: With Deep Q-Networks and LLMs, we’ll be updating a Neural Network’s weights using an optimizer instead of a table.

def update_q_table(

q_table: np.ndarray,

state: int,

action: int,

next_state: int,

reward: float,

alpha: float,

gamma: float,

):

"""

Updates the action-value (Q-table) using the Q-learning rule.

The agent's exploratory, 'off-policy' action is chosen in the

`choose_action` function. This `update_q_table` function then provides

the learning step.

The learning rule is always greedy. It updates the value of the action

taken (`action`) by looking at the best possible future value it can get

from the `next_state` (i.e., `max(Q(next_state, a))`).

This allows the agent to explore new actions while always learning and

improving its estimate of the single, optimal policy.

"""

old_expected_q_value = q_table[

state, action

] # Get the current value for the current state-action pair

# Assume that in the next state, the model will pick the action with the max:

next_max = np.max(q_table[next_state])

# Temporal difference target is the reward of this state, plus a discounted assumption of the next max value

td_target = reward + gamma * next_max

# The error between the target and what we thought the target was:

td_error = td_target - old_expected_q_value

# Update to a new adjusted value, but don't just snap to it. Apply another downweighting factor

new_adjusted_q_value = old_expected_q_value + alpha * td_error

q_table[state, action] = new_adjusted_q_value

Two Additional Key Concepts in our Q-Learning Implementation#

This code implements two other key ideas, temporaal difference and the Bellman equation.

Temporal Difference (TD) Learning#

Our algorithm uses Temporal Difference (TD) Learning. This means we “update a guess based on another guess.” We don’t wait until the end of the episode to learn. Instead, we update the value of the current state (state) using the estimated value of the next state (next_state).

The alternative, called Monte Carlo methods, would be to wait until the agent falls into a hole or finds the prize, and only then update the values for all the steps taken in that episode. TD learning is often more efficient as it learns at every step.

The Bellman Equation#

The update rule in our code is a direct application of the Bellman Equation. In simple terms, the equation states:

The value of a choice is the immediate reward plus the discounted value of the state you land in.

Our update_q_table function implements this: td_target = reward + gamma * next_max. We are optimizing our current action’s value based on the immediate reward plus an estimate of future potential. This process of using an estimate to update another estimate is called bootstrapping.

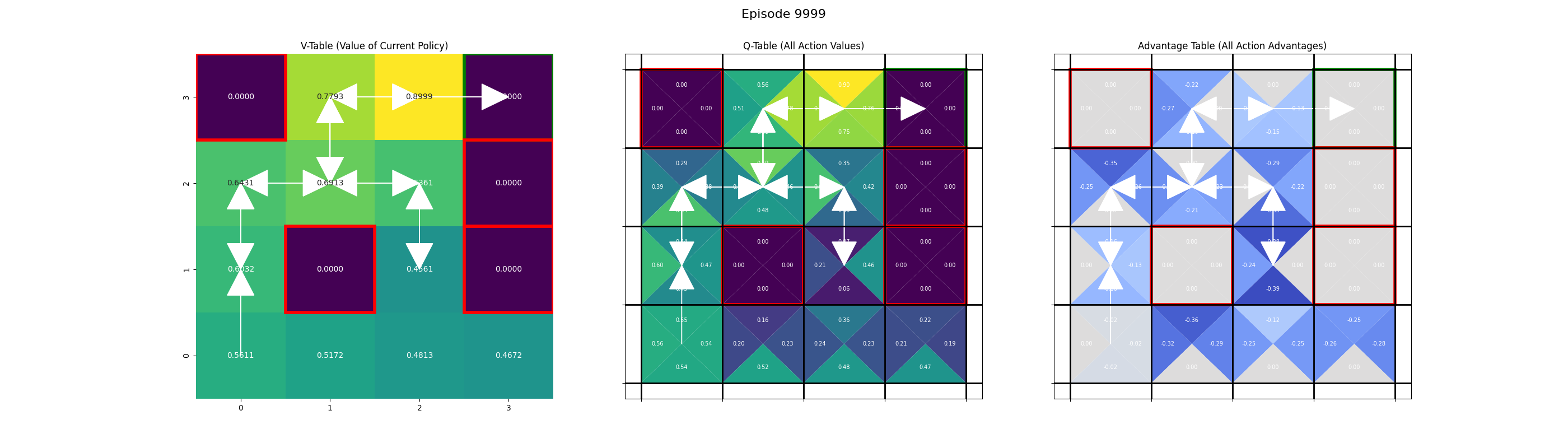

Advantage#

Another key concept is the idea, and mathematical definition of advantage.

A challenge in reinforcement learning is that the estimation of Q-values is often unstable (high variance). Advantage is a concept that helps to mitigate this. The advantage of an action \(a\) in a state \(s\) is the difference between the Q-value for that state-action pair and the value of the state:

For Ice Maze Q and V table this is what it looks like in code, a relatively simple one line.

def calculate_advantage(q_table):

"""Calculates the advantage table: A(s, a) = Q(s, a) - V(s)."""

v_table = np.max(q_table, axis=1)

return q_table - v_table.reshape(-1, 1)

The advantage tells us how much better it is to take a specific action \(a\) compared to the average action from that state. This can help in a few ways:

Reduces variance: It can help to reduce the variance of policy gradient updates in more advanced algorithms.

Better for learning: It can be more stable and efficient to learn the advantage instead of the Q-values directly.

Advantage is not not strictly needed for Q-learning, and in other Ice Maze implementations it is not introduced at all because for a simple problem like this the policy can be learned quite readily without it. However with algorithms used for LLMs, like PPO and GRPO, advantage is a crucial calculation that speeds up learning efficiency. As you’ll see later a change in the way advantage is calculated was one of the key contributions made by the DeepSeek authors. For this reason, and because it’s a fundamental concept in many modern RL algorithms, we introduce it now.

Reinforcement Learning Loop#

After all that, here is the algorithm itself! The biggest choice here is number of episodes – how many times the model will try to traverse the maze.

# --- Main Script ---

env = gym.make(

"FrozenLake-v1", is_slippery=True

) # we're "renting" the FrozenLake environment from Gymnasium

# --- Hyperparameters ---

num_episodes = 10_000

alpha = 0.1 # how much we value new information

gamma = 0.99 # how much we value future rewards

epsilon = 1.0 # how often we explore

epsilon_decay_rate = 0.0001

min_epsilon = 0.01

# --- Frame Saving Setup ---

save_interval = 1000

output_dir = "output"

os.makedirs(output_dir, exist_ok=True)

# --- Identify Goal and Hole States ---

desc = env.unwrapped.desc.astype(str)

grid_size = desc.shape[0]

goal_coords = [

(r, c) for r, row in enumerate(desc) for c, char in enumerate(row) if char == "G"

]

hole_coords = [

(r, c) for r, row in enumerate(desc) for c, char in enumerate(row) if char == "H"

]

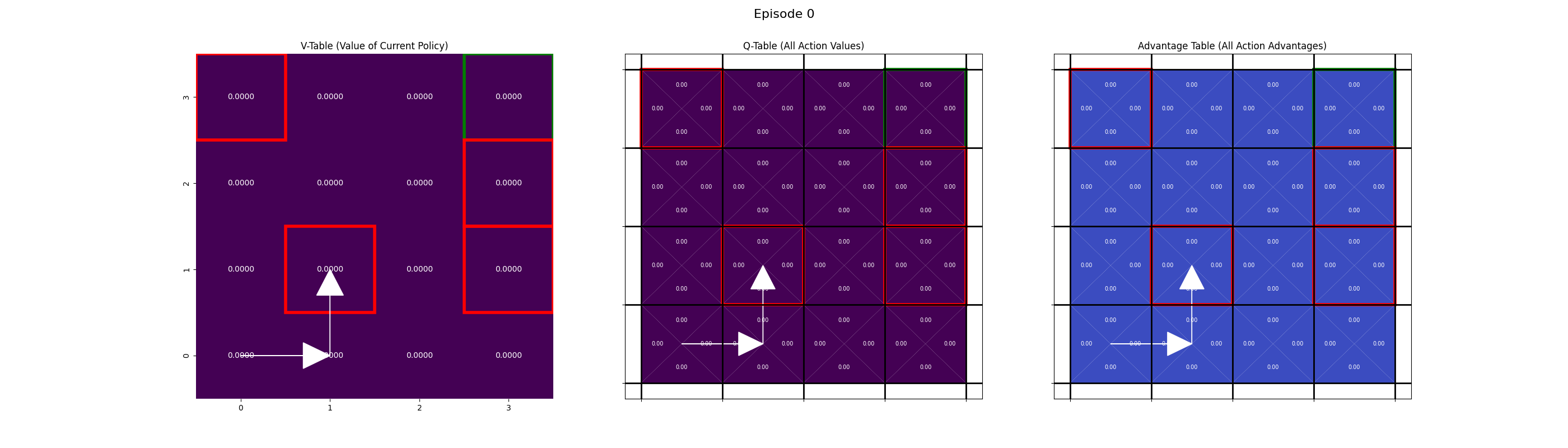

We initialize the q table here with zeros. This indicates that we don’t know anything about the goodness of each state:

q_table = np.zeros([env.observation_space.n, env.action_space.n])

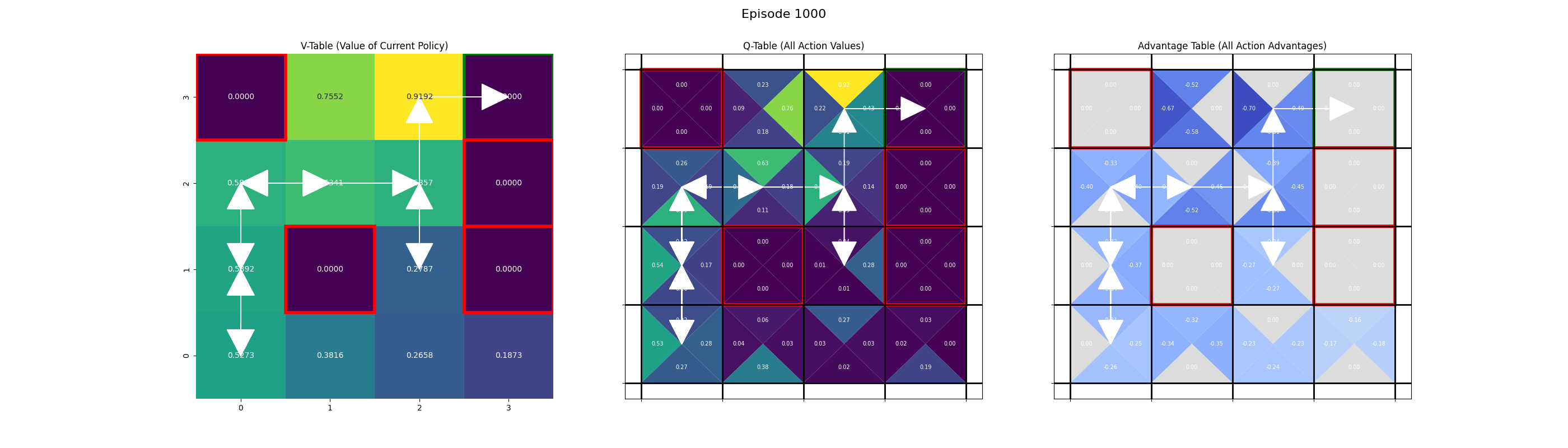

From here we start the training loop, where the agent takes many actions, going through many states in thousands of episodes, to finally learn the correct path:

from IPython.display import Image, display

# --- Training Loop ---

for episode in range(num_episodes):

state, info = env.reset()

terminated = False

truncated = False

trajectory = [state]

while not terminated and not truncated:

# Take an action and enter the next state and obtain a reward

action = choose_action(q_table, state, epsilon, env)

next_state, reward, terminated, truncated, info = env.step(action)

# Update the q table based on the new information

update_q_table(q_table, state, action, next_state, reward, alpha, gamma)

# Update current state

state = next_state

trajectory.append(state)

epsilon = max(min_epsilon, epsilon - epsilon_decay_rate)

# --- Save a frame at specified intervals ---

if episode % save_interval == 0 or episode == num_episodes - 1:

print(f"Saving frame for episode {episode}...")

advantage_table = calculate_advantage(q_table)

value_table = np.max(q_table, axis=1)

plot.save_frame(

episode,

value_table,

q_table,

advantage_table,

trajectory,

grid_size,

goal_coords,

hole_coords,

output_dir,

)

image_path = os.path.join(output_dir, f"episode_{episode}.png")

display(Image(filename=image_path))

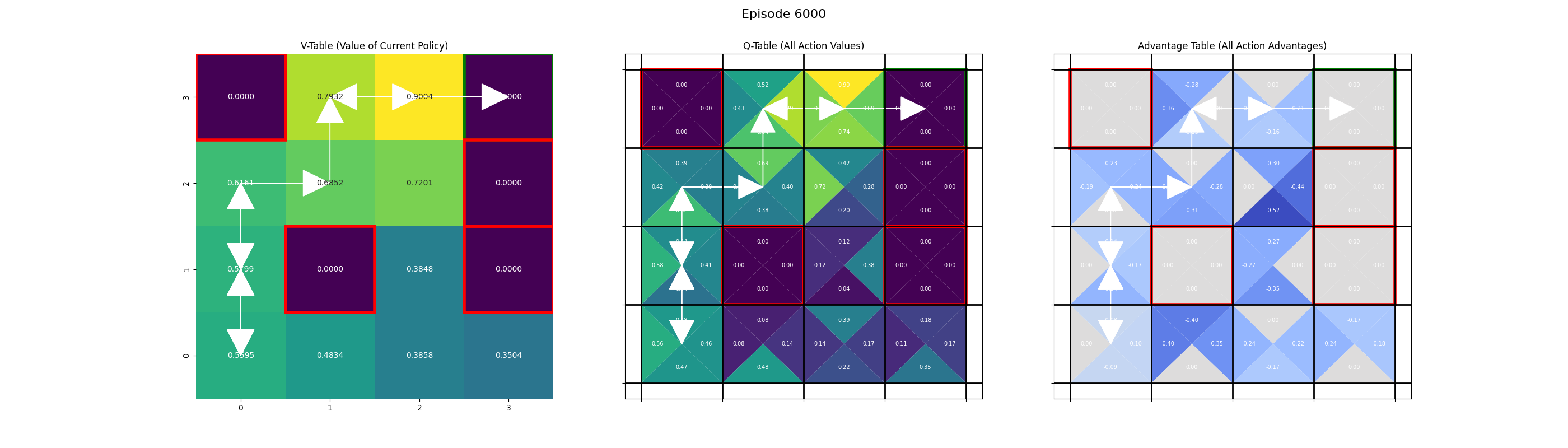

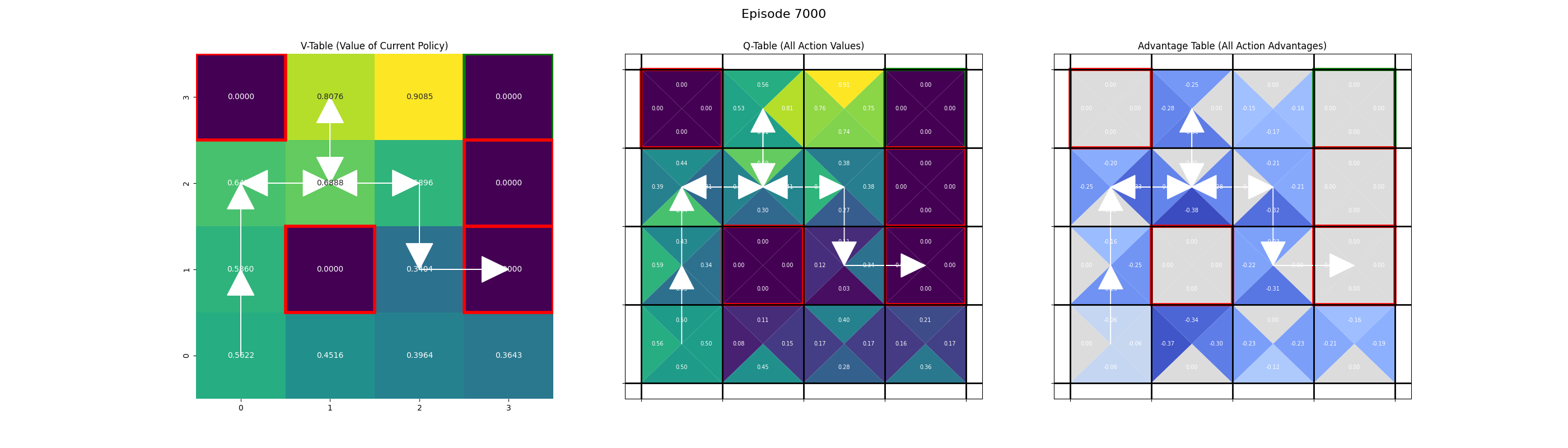

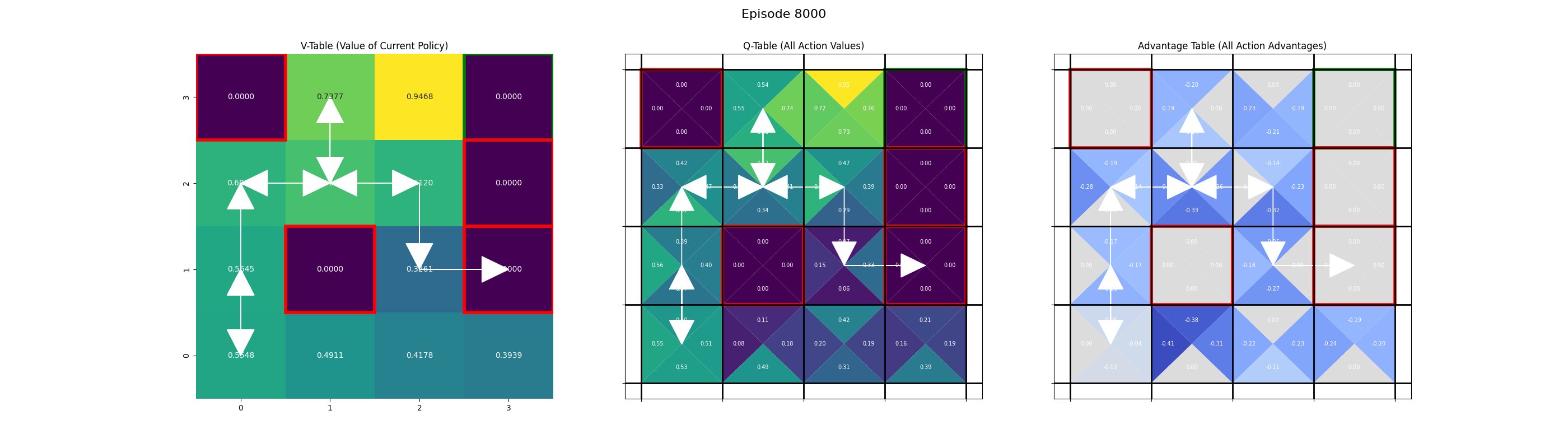

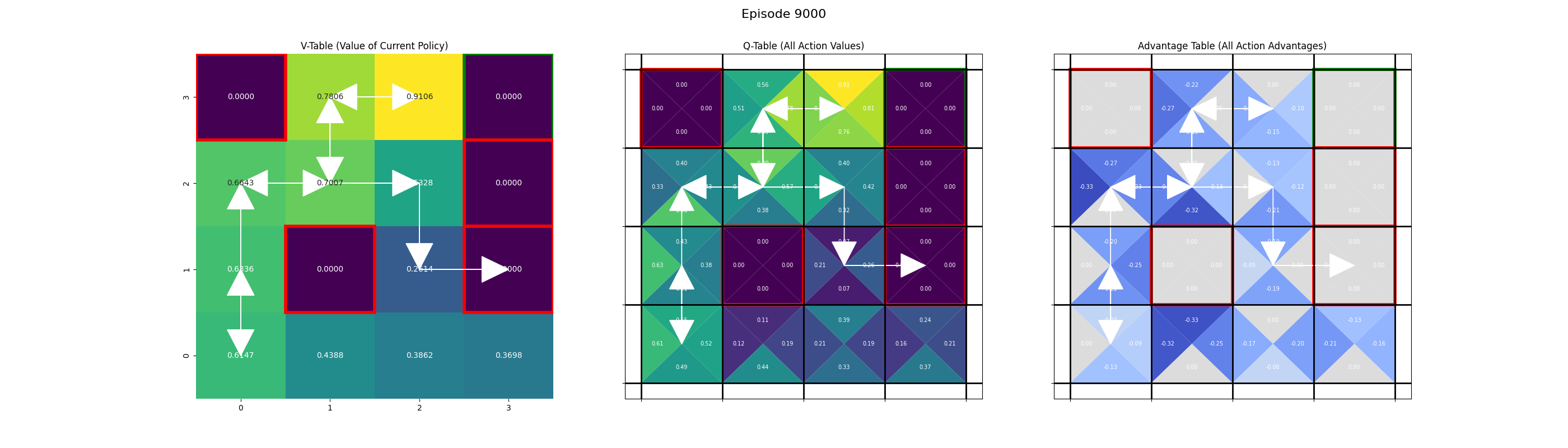

Saving frame for episode 0...

Saving frame for episode 1000...

Saving frame for episode 2000...

Saving frame for episode 3000...

Saving frame for episode 4000...

Saving frame for episode 5000...

Saving frame for episode 6000...

Saving frame for episode 7000...

Saving frame for episode 8000...

Saving frame for episode 9000...

Saving frame for episode 9999...

Evaluation#

Now that the agent has finished training, we should evaluate its performance. During training, we used an epsilon-greedy policy to allow for exploration. For evaluation, we set epsilon = 0, meaning the agent will always choose the action with the highest Q-value it has learned. Note that because the environment is slippery (i.e contains randomness), the success rate will not be 100%, even with an optimal policy, but should be significantly higher than random chance.

# --- Evaluation Loop ---

num_test_episodes = 100

success_count = 0

for episode in range(num_test_episodes):

state, _ = env.reset()

terminated = False

truncated = False

while not (terminated or truncated):

# Always exploit: pick the best known action (epsilon=0)

action = np.argmax(q_table[state])

# Take the action

state, reward, terminated, truncated, _ = env.step(action)

if terminated and reward == 1:

success_count += 1

print(

f"Success rate over {num_test_episodes} test episodes: {success_count / num_test_episodes * 100:.2f}%"

)

Success rate over 100 test episodes: 68.00%

Typical values for FrozenLake-v1 with ice=slippery and an optimal Q-table are around 70-80%, so we’re in this ballpark.

Suggested Prompts#

What is the history of Reinforcement Learning?

How has RL changed as models have become larger?

What concepts in this notebook are used later in the LLM training chapters?

References#

Frozen Lake - Frozen Lake implementation from the Farama Foundation showing the setup of the challenge